Journalists from The Irish Times, a leading Irish newspaper, visited Metinvest Group’s enterprises in Pokrovsk and returned with a report that once again highlights the day-to-day heroism of miners who continue to work for Ukraine’s economy despite the hostilities.

Kateryna Tolmachova says she always wanted to work in the vast coal mine that supports her hometown in eastern Ukraine, and the creeping approach of the front line will not make her quit.

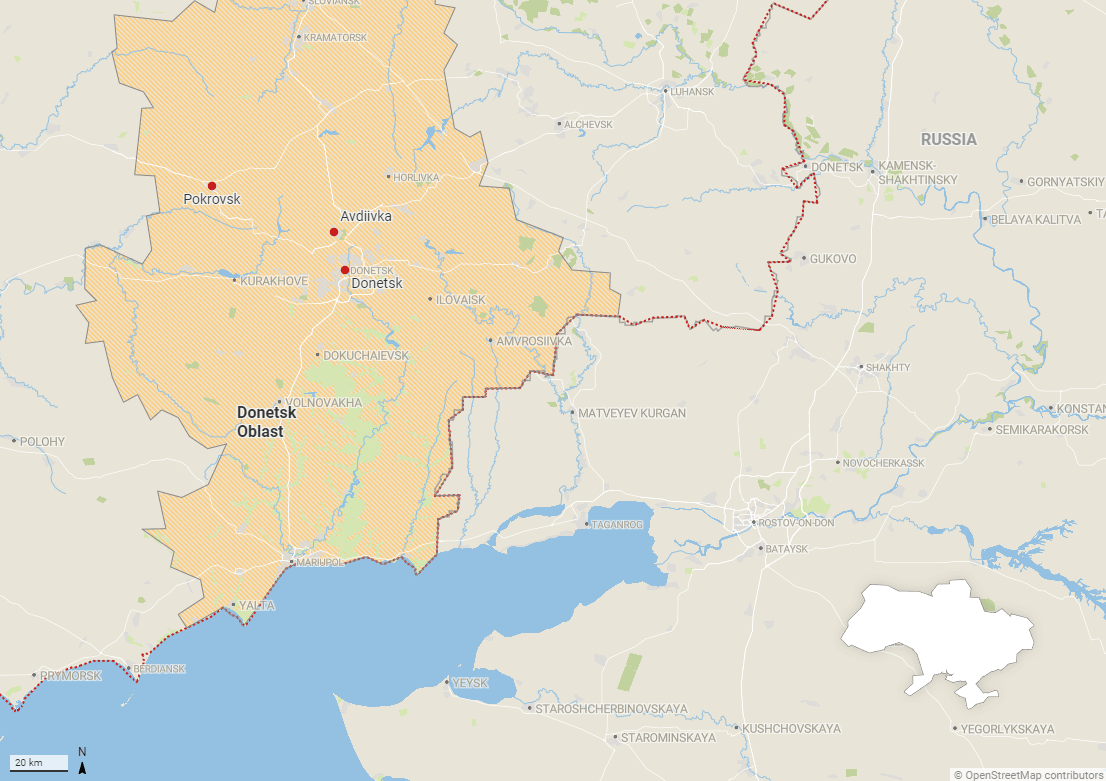

Pokrovsk is in the sights of Russian forces that seized Avdiivka in February and are now about 40km away, but there is no sign of panic in a long-time powerhouse of Ukrainian mining that now also serves as a military stronghold.

“I dreamed of working here when I was little and was so proud to get a job,” says Tolmachova, who is deputy head of a section that looks after pumps, compressors and cranes at the Pokrovsk coal mine, which is Ukraine’s biggest.

“Thankfully we’re still operating normally. Of course, we hear explosions sometimes and can feel worried. But I don’t want to leave my home and my job. In fact, I never thought for a moment that I might leave.”

Pokrovsk, like most of the Donetsk region, was built on mining and heavy industry, and the reputed toughness of the area’s people has been tested since Russia fomented fighting in 2014, eight years before its all-out invasion of Ukraine.

When the Maidan revolution pivoted Ukraine towards the West in 2014, Moscow seized Crimea and sent fighters and weapons into the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.

With Ukraine in flux after the revolution, heavily armed Russian-led militias seized parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions and announced the creation of “people’s republics” that rejected Kyiv’s rule and declared allegiance to the Kremlin.

Pokrovsk, which was then still called Krasnoarmiysk, narrowly avoided capture by the militants as they established a separatist “capital” in the city of Donetsk, 60km to the east.

From summer 2014 until February 2022, the front line in Donbas barely moved, and coal from Pokrovsk kept flowing to a huge coking plant in Avdiivka. From there, millions of tonnes of coke each year then moved 130km south to Mariupol, where the Azovstal factory by the Azov Sea made steel products that were shipped to the world.

Russia’s military bombarded and then occupied Mariupol two years ago and did the same to Avdiivka this winter. Azovstal and the Avdiivka Coke plant are now in ruins and most Donbas mines are occupied or destroyed, but Pokrovsk still digs around the clock, seven days a week, and produced more than five million tonnes of coal last year.

“My sense of responsibility for myself and for the people I work with every day has changed,” Tolmachova says of the impact of the full-scale war.

“It can be very hard, so we provide moral support for each other. Sometimes colleagues say they want to quit and leave, but we try to reassure them that we believe in our armed forces and in our Ukraine, and that everything will be all right,” she adds. “The staff are more united now. We know that our work is important not only for Pokrovsk and Donbas but for the whole country.”

Coal from Pokrovsk now feeds factories in other regions of Ukraine, including plants of Metinvest Group that owns mines and supplies Ukrainian troops with equipment ranging from bulletproof vests to reinforced shelters.

At the coal face up to 1km underground and in the vast engineering halls that keep the machinery running, the work is hard and potentially dangerous, and brightly coloured signs on the walls remind staff that a loss of concentration could be deadly.

They are not keen to talk about the war, but there is no escaping it: about 1,000 of the mine’s 10,000 pre-war employees are in the army, and Pokrovsk is a frequent target for Russian rocket fire.

For now, Pokrovsk remains out of range for regular Russian artillery, and it is bustling with soldiers and volunteers and with locals who run its busy shops, markets and cafes, as well as with workers and support staff from the mine.

“I’ve been here for 29 years. I started as a welder and then moved on to operating machinery. I spent 22 years working underground and then transferred to the engineering workshop,” says Oleksandr Chura, a 49-year-old mechanic of a section that repairs downhole equipment.

“I feel a bit of nostalgia for working underground and at night I sometimes still dream about it. I enjoyed it when I was young, but it gets harder with age and as your health declines. The further you go, the hotter it gets, and it’s not for me now,” he adds.

“The best jobs in town were always at the mine – the best wages, healthcare, benefits and so on,” Chura recalls.

“The mine is working as it did before the war. We’re doing everything to keep bringing up the coal. That chain is still there – dig the coal to make coke to make metal. We’re still producing like before and we hope to keep doing it for a long time.”

The vast complex is a little like a town within a town, and even has its own Orthodox chapel. The Group’s buses bring in workers from surrounding villages, its own security team patrols the site and outsiders asking questions are treated warily.

Oksana is a lift operator. When the bell in her booth on the surface rings four times, she knows the miners are ready to come up from the coal face about 800m below.

Three minutes later the lift arrives and they emerge, grimy faced, from between red gates emblazoned with the yellow trident that is a national symbol of Ukraine. Above their heads a sign reads: “Look after yourselves! People are waiting for you at home!”

Then they walk through revolving grey metal doors into a hall where, until renovation work began, one wall was lined with taps that dispensed hot black and hibiscus tea. They hand their lamps back to a supervisor, take a shower and leave their overalls in a laundry equipped with cavernous washing machines and dryers.

The routine is essentially the same as when the mine opened in 1990, a year before the collapse of the Soviet Union. Ukraine hopes Pokrovsk will feed its industry with coal for decades more from estimated reserves of 200 million tonnes.

For that to happen, the country’s army must stop Russia’s creeping advance despite being hampered by ammunition shortages caused by a Republican-inspired halt to US military aid and Europe’s failure to rapidly expand arms production.

When Avdiivka fell in February, Metinvest chief executive Yuriy Ryzhenkov said Russia’s gains were “alarming”.

“We are concerned with how the situation develops on the ground but we are also very concerned with the lack of commitment of some of our allies,” he told Reuters at the time. “The message is pretty clear ... please don’t let us down, it is as simple as that”.

Despite the uncertainty, 18-year-old apprentices Ivan, Yaroslav and Vladyslav see their futures at the mine and travel to Pokrovsk by company bus from nearby Myrnohrad, a town even closer to the fighting.

They all say they want steady work and a good salary, and Vladyslav is continuing a family tradition: “My grandfather and father worked here, and I’m following in their footsteps.”

Pokrovsk was long regarded as a prosperous part of Donbas because of the decent wages paid by the mine, and its continued operation – combined with the presence of many soldiers with some money to spend – means the town is still full of life.

“A lot of people left [earlier in the war] but came back to Pokrovsk because they couldn’t find work or a place to live somewhere else,” says Tolmachova, sitting on a bench in spring sunshine outside the chapel in the mine complex.

“Practically every family in town has someone who works here or worked here before. It’s important that we keep going – it means having a job, a wage and certainty about what you’ll be doing tomorrow – not everywhere in Ukraine has that.”